Match Analysis

Those of you sports nuts who know all about Opta, ProZone and match analytics may find it hard to believe but once upon a time there was no computer analysis of sports matches – that’s right, nothing! Charles Reep was the first person to make an impact on match patterns – notably the so-called ‘long-ball game’ – through his historic analysis of soccer play in the 1950s but hand-written notes were all that would-be analysts could use back then.

In the early 1980s, two major technologies were brought together to advance the science of match analysis: the first was the choreographic tool of notation, mainly associated with recording dance patterns, that was modified to record sport match patterns. In the early 1980s, coach Jake Downey developed a badminton notation and about the same time I developed a notation for lacrosse. These notation systems allowed us to store complete records of games, rather like musical scores, and to pore over these after each game to search for playing strengths and weakness. However, I was able to extend the technical analysis through the second innovation – the BBC desk-top microcomputer which could be used to crunch match data in seconds rather than hours.

Pilot testing the lacrosse notation system

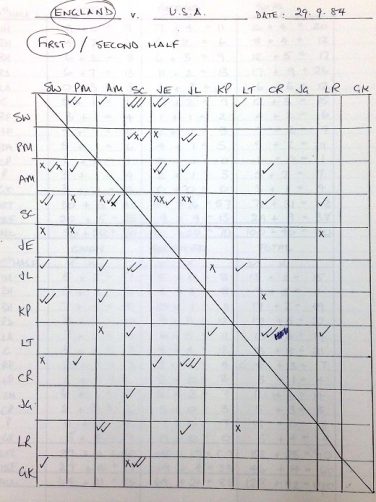

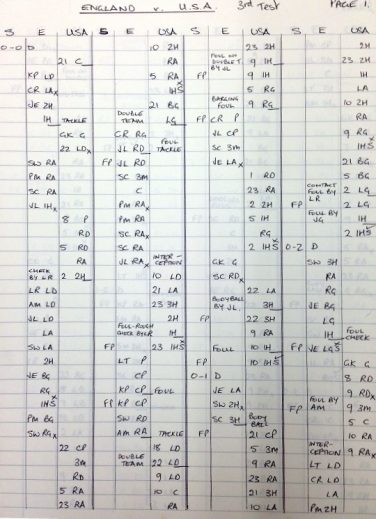

Thanks to a grant of £1200 from the National Coaching Foundation I was able to spend some time developing and pilot testing the lacrosse notation system around 1983-84. It was a laborious process! First, I divided up the field of play into sections and decided on a set of symbols to represent these, the players and the techniques. Next, I used a hand-held dictaphone to speak a running commentary of these elements from the pitchside. After each game, I replayed the tape and notated the match using a set of vertical staves and the set of symbols: I called this system ‘BRACstat’. A full match of 50 minutes would cover 7 or 8 pages. From the notated score I could then extract frequency analyses of passing and shooting patterns, individual player profiles and various other things. It was possible to read the score to see different tactical ploys, e.g. fast breaks, zone defences, and whether or how they were effective. I used this paper-based system during two stints as Assistant Women’s Lacrosse Coach at Harvard University in the USA in 1983 and 1984 and also tied the resulting match data in to social psychology testing with the women’s team there. Meanwhile, my colleague Anita White (then at Chichester) was working on her own analysis system for women’s hockey: we presented a joint paper at the 1984 Olympic Scientific Congress in Eugene, Oregon.

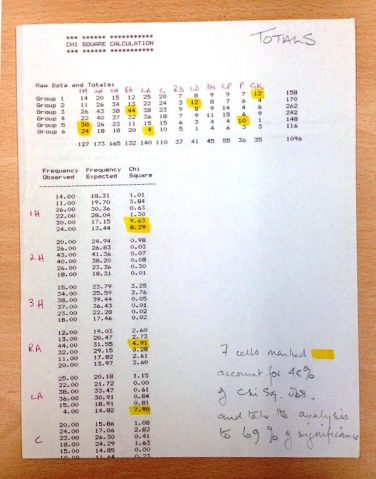

My colleague Dr John Alderson at the then-Sheffield City Polytechnic wrote a software programme for the BBC microcomputer and we typed in all the patterns from the paper version of the BRACstat score and the software did the rest, yielding print outs of various game parameters that I could then use to inform my coaching. I developed the system at some regional tournament games and went on to use it when I was England coach. John designed a prototype hand-held touch type system for squash which could be used to input match data in real time from the court gallery, with analysis made available to the player and coach during the one minute break between games. Shortly after this, a similar kind of rugby analysis was developed by now world-famous Keith Lyons: Keith has gone on to lead the world in rugby analysis, advising teams at the recent men’s Rugby World Cup and working for many of the international rugby coaches. He also held a position at the Australian Institute for Sport in Canberra for several years, tasked with researching and developing match analytics.

Growing at a rapid rate

During the late 1980s and 1990s match analytics grew at a rapid rate as computer technology, statistics and sport science expanded their symbiotic relationship. Many professional soccer clubs began to employ match analysts and now it is unthinkable for professional sports of all kinds not to have on their staff at least one analyst armed with the most sophisticated computer technology. Their work is often kept secret for reasons of possible industrial espionage but scientific organisations like BASES have embraced analysts in their professional structures.

I wrote a few papers on match analysis, but my research career took a very different turn when I was sacked as national coach for not winning the 1986 Women’s Lacrosse World Cup! It was a severe blow after 25 years in the sport but I moved in a new direction and have since completed almost 40 years of research and activism in child abuse and violence prevention in sport. Looking back, I am proud of my few years of match analysis work in Women’s Lacrosse. It certainly helped me and many of my national squad members and perhaps helped to boost the acceptance of science in sport.

This article was originally posted on the Brunel University London Special Collections blog and is reproduced with their permission. Further details on the Match analysis items held at the Brunel Library in Special Collections can be found by following the link.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page