Tull made a swift transition from sport to war. In December 1914, he abandoned his football career, and volunteered to join the British Army, enlisting in the 17th (1st Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, alongside many other professional footballers (WO 95/1361).

Posted to the Western Front

On 18 November 1915 Walter was posted to the Western Front, as part of the 33rd Division, 100th Brigade. Football helped counteract the boredom and monotony of life behind the lines, as many makeshift games were played. Soccer became an important feature of the men’s free time and was often seen as a galvanising force at others.

The dignity and strength with which Walter confronted blatant and vicious racism on the pitch were to serve him well on the battlefield. He was evacuated home with shell shock on 9 May 1916, returning to France on 20 September to fight in the 1st Battle of the Somme, where he survived the slaughter and was praised for his bravery. Walter showed he was a fine leader of men, receiving rapid promotion to Lance Corporal on 12 February 1915, to Corporal on 4 May 1915, then to Lance Sergeant just three days later.

Mounting casualties

With the mounting casualties the promising NCOs were targeted as replacement officers and now something extraordinary happened. Towards the end of 1916 Walter was invalided home with trench fever. Upon leaving hospital on 26 January 1917 he was admitted to the officer cadet training school at Gailes in Scotland, to begin his training for a commission. This was unprecedented, indeed it was technically impossible. In general black officers did not command white troops and in the language of the time the 1914 Manual of Military Law specifically excluded ‘Negroes’ from exercising actual command as officers. Yet Tull’s superior officers must have recommended him and, as a result of his service on the Somme, at Messines Ridge and Passchendale, he was commissioned in May 1917. He became the first black infantry officer in the British Army, although he was not the first black officer, as at least two were serving in the Medical Corps. Nevertheless this was quite some achievement.

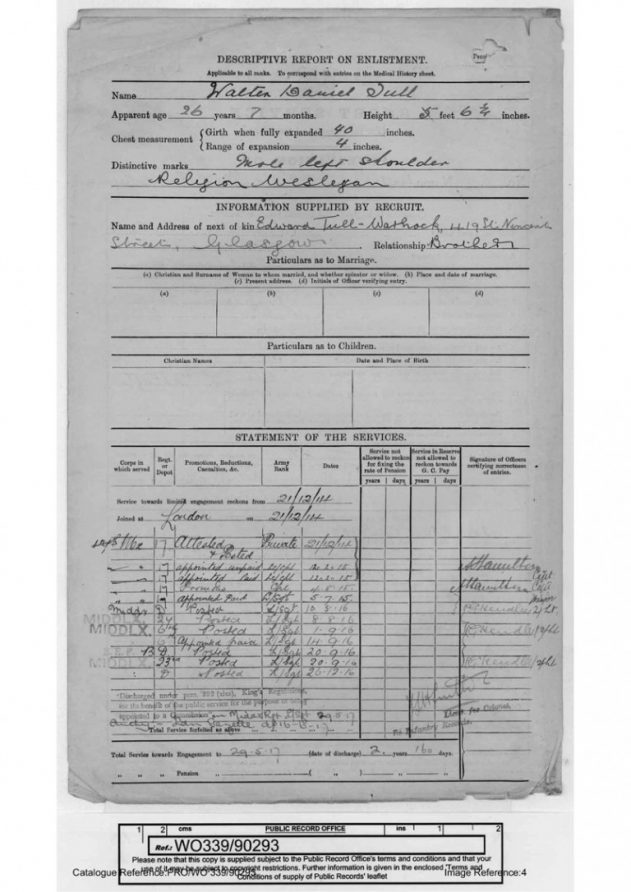

According to his service record (WO 339/90293) and as a newly promoted 2nd Lieutenant he was posted to the Italian front with the 23rd (2nd Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, where he was mentioned in dispatches for his ‘gallantry’, ‘coolness’ and his ‘bravery under fire’ with which he led his men in the first Battle of Piave.

In 1918 he and his men were posted back to the Western Front, where they fought in the second Battle of the Somme. The end of the First World War was in sight but tragically Walter was not to see it. On 25 March 1918, the 29 year old was killed in no-man’s land, near Favreuil, whilst leading a counter attack against the German positions (WO 95/2639). His men held him in such high regard that they risked their own lives to try to retrieve his body, which was never found. Unfortunately the recovery had to be abandoned under increasingly heavy machine gun fire. For many years his only memorial was his name on a wall at the Arras Memorial set up by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

An emotional report

Tull’s commanding officer reported to Edward Tull, in startlingly emotional terms, on ‘how popular’ he was throughout the battalion. He was brave and conscientious…..’The battalion and company have lost a faithful officer, and personally I have lost a friend’.

Society at large probably did not consider the untimely death of a black working class orphan a loss worthy of permanent commemoration, and he passed from the public mind. It was not until over 80 years after his death that a permanent memorial was unveiled, near the south car park, at Sixfields Stadium, the centrepiece for the Garden of Rest at Northampton Town Football Club.

The specific qualities that made him remarkable include most of the virtues traditionally claimed as Anglo-Saxon; modesty, dignity, honesty, quiet determination, courage, in short a stiff upper lip. But he was loved more than that – he was a figure of extinguishable spirit, who was loved by Britons, black and white, and gave his life for his country. He must have been a remarkable man.

Legacy

Walter’s true legacy is the influence and example he is for everyone today. Not just young footballers, not just young black people. Everyone! It took a very special person to surmount the barriers of class and colour and to establish themselves at the highest level in early twentieth century Britain.

This article has been adapted from the National Archives blog, and is reproduced under the terms of the Open Government License.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page